No time to read? Listen to the podcast.

Aside from an occasional volcanic eruption in Hawaii, they’re not making any more real estate here in the U.S. of A. That’s what makes it so expensive. With that in mind, if your head is still filled with trivia from the 1960s, your neck is supporting a gold mine.

Like real estate, they’re not making any more trivia, either.

No, those hundreds of new Jeopardy! questions each year aren’t trivia. Neither are the pretenders to the throne pouring out of the weekly trivia nights at local pubs. And while we can’t stop celebrities from driving into buses, fire hydrants, and other city property, “What is the longitude and latitude of the lamppost Hallie Berry ran into on Sunset Boulevard?” isn’t a legitimate trivia question.

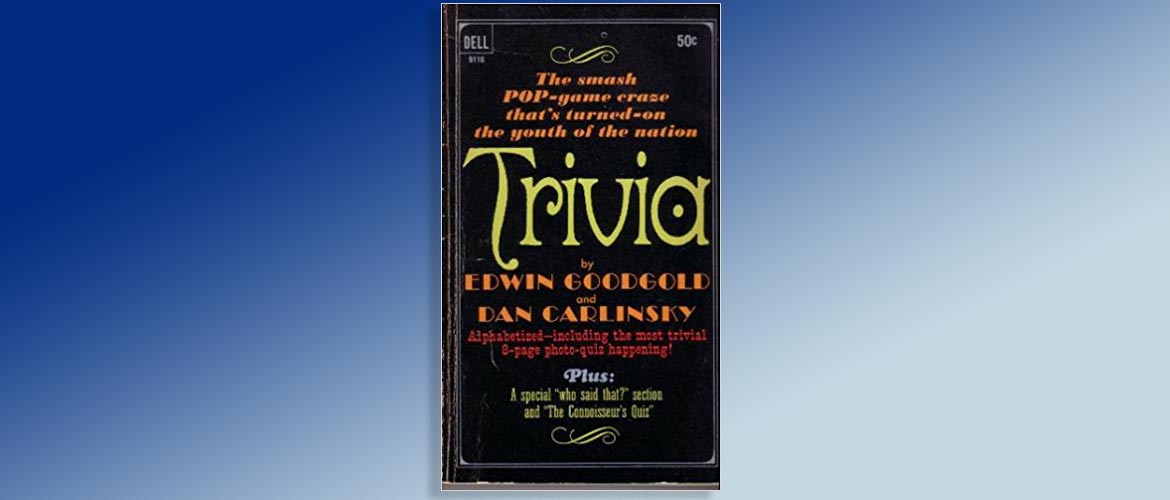

That’s the state of trivia according to Dan Carlinsky, whose name is arguably a trivia answer in itself. He and fellow student Ed Goodgold started the trivia craze on the Columbia University campus in 1965. Well, to be accurate, the proper phrasing is “Who capitalized on the trivia craze in 1965?”

“Minutiae are questions like, ‘Which state is the largest consumer of Jell-O, or what was President Chester Arthur’s middle name?’”

Trivia entered our collective consciousness in a February 5, 1965 article in The Columbia Daily Spectator, the university’s student-run newspaper. In it, Goodgold described the endless gatherings in which students spent their nights in one of the dormitory lounges challenging each other with minute details from their youth.

“Whenever the raw nerve of any hallowed memories are touched by these questions, contestants usually writhe in ecstasy. Some have even been known to salivate,” Goodgold wrote. It was the first clue that trivia was different than minutiae, those arcane details that are wielded like a sword to demonstrate intellectual superiority. Trivia demonstrated a mastery of the arcane that lurked inside shared childhood experiences.

Let’s back up. Childhood experiences? These students were still teenagers. “This was the 1960s and the students were talking about their childhoods in the 1950s,” Carlinsky said.

If there was any kind of trivia volcanic eruption, that was it. The nostalgia factor. It was nostalgia that turned dictionary-definition trivia into Trivia with a capital T.

“Ed and I distinguished between what we called the flower of trivia and the weed of minutiae,” Carlinsky said before offering up a working definition of Trivia. “Minutiae are questions like, ‘Which state is the largest consumer of Jell-O, or what was President Chester Arthur’s middle name?’ The answer to both of those questions is who gives a sh*t?

“Whereas, if I ask you what was the slogan on Paladin’s business card, even if you can’t answer it, you kind of feel that you should because you used to watch that show on television.”

And while the question-and-answer format for displaying your trivia expertise (while trivializing that of your opponent) pre-dates even quiz shows, Carlinsky postulated that the tools we used to make trivia are falling into decay and disuse.

“It’s because of the splintering of popular culture. Where there used to be a handful of television channels, which the whole family watched together, there are now 500 cable channels, plus YouTube, Netflix, and so on,” Carlinsky said.

Aside from a handful of events—the Super Bowl and presidential election returns are the only two that come to my mind—there are few things that bind Americans together the way radio, movies, and television did when media options were limited, forcing families to share the same cultural touchstones.

Carlinsky agreed. “Families grew up with television together because there wasn’t that much on television and there was only one television in the house. Now in a large portion of the country, not everybody, but your basic suburban white picket fence, 2.5 kids and the dog, those 2.5 kids now have 2.5 televisions in their own bedrooms. It’s not good for the future of trivia, though the kids probably don’t mind.”

We’re not going to stop making popular culture, and the drive to turn that culture into formal and impromptu trivia contests are too ingrained in our psyches to become an item of nostalgia, themselves. (Ken Jennings, Jeopardy!’s former—and currently second—highest-earning contestant, wrote in his book Brainiac: Adventures in the Curious, Competitive, Compulsive World of Trivia Buffs that the notion of trivia dates back to the Roman goddess Hecate “in her role of guardian of the crossroads…because a trivium, or public crossroads, was literally a ‘common place.’”)

While we might have reached the sixth, and final, day of trivia’s creation, our fascination with question-and-answer games has hardly faded, leaving us with a single choice: carrying on with minutiae.

“The weeds,” Carlinsky said, somewhat wistfully, “have overtaken the flower garden,” transforming the nostalgia that defines trivia into nostalgia for trivia, itself.

Start your Sunday with a laugh. Read the Sunday Funnies, fresh humor from The Out Of My Mind Blog. Subscribe now and you'll never miss a post.

Mind Doodle…

During an appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, Woody Allen disclosed that Count Dracula’s first name was Voivode. He’d gleaned this information from Goodgold and Carlinsky’s first trivia book. What Carson and Allen didn’t know was that after the book went to press Carlinsky discovered he’d made a mistake during his research. Voivode was an Eastern European word for “Count.”