Quick. I say diamond cutting and you say…?

Quick. I say diamond cutting and you say…?

Right. That 1977 Lincoln Continental commercial with the diamond cutter working in the back seat. He squints through his magnifying lenses, raises his hand and brings down his mallet.

At that critical moment guess what’s going through his mind.

I hope these magnifying lenses don’t make my eyes look fat.

Come on. The guy’s an actor. If he were a real diamond cutter, here’s what he’d be thinking.

Economics.

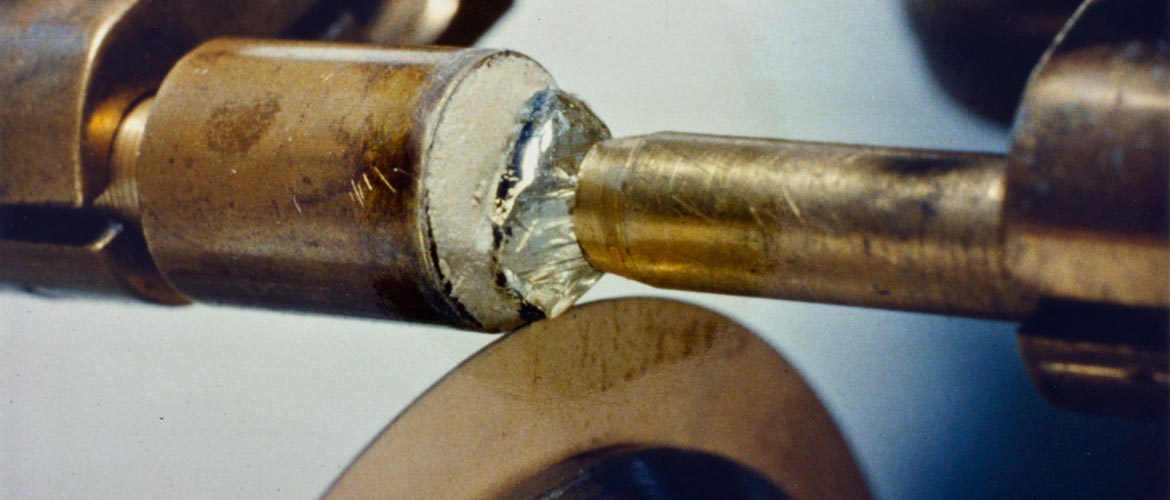

That’s the word from veteran diamond cutter Barry Rogoff. “We cut diamonds to enhance their beauty,” he told me as he brought out several stones for me to examine. “When the crystals come out of the ground they’re rough diamonds. They have different types of shapes. But you’ve got to unlock the brilliance and scintillation from the rough stones.”

In one motion he has the ability to turn the stone into little more than pocket change. Which is why I was surprised I had to bring up the question of pressure.

How Rogoff does that is based on that E-word. “Is it going to be economically feasible and viable if we cut it this way or that way?” he said.

Rogoff came to the New York City from Johannesburg, South Africa in 1976. By that time, he had over 10 years of experience with diamonds in the rough. Today he presides over his own shop on Hill Street, in the heart of Los Angeles’s jewelry district.

“I learned at a highly recognized diamond cutting factory called Gustav Katz.” He was 15 when he walked in the door. “In the mornings I studied all aspects of diamond cutting, from the physics of diamonds to the buying of raw stones. In the afternoon I worked with my journeyman. This part of my education took three years. It took another two years years to hone my skills enough to be a serious cutter.”

Now he’s an expert on increasing the value of previously-cut stones, like the one he put in front of me. It was a trifling little bauble, a 4-carat diamond I could imagine my wife wearing while buying organic burritos at Costco. This stone was so clear it would have disappeared on Rogoff’s desk were it not for the way its facets played games with the light.

“That’s a D color,” he said. “It doesn’t get any better than that.”

Rogoff was ready to improve upon nature nonetheless. “It has potential. When I remove this bruise, and these chips, and an indented natural…” It was scary, as if he were seeing the diamond in some different universe. “Once I take these out, I improve the value.”

In my circles, the idea of “improving the value” means refacing the kitchen cabinets.

“Presently, this diamond is worth $50,000 a carat. But once I improve the clarity it will go from $50,000 a carat to $66,400.” Lest you forget, it’s a 4-carat stone. Rogoff was going to bump its current value by $65,600. More than it was worth in the first place.

Forget the cabinets. That’s a new kitchen.

Here’s the challenge, though. Rogoff doesn’t own the stones he cuts any more than a contractor owns the kitchen he works on. But there are no do-overs in Rogoff’s world, He doesn’t get to cover his mistakes with paint or sheetrock. In one motion he has the ability to turn a stone into little more than pocket change. Which is why I was surprised I had to bring up the question of pressure.

“People in the trade understand the risks. They know what the game is. Diamonds are dangerous to cut. They have internal stress and strain, some more than others, so they are subject to fracturing. But when something like that happens, and it doesn’t happen too often thank goodness, we consider it an act of God. There’s no negligence.”

I could tell that Rogoff, who framed pressure as part of his job (“I’m a professional. This is what I do.”), had a larger concern than legalities.

“If I make a mistake, it’s the worst feeling in the world. You want to throw up.” I pointed out that even the best baseball pitcher gives up that home run ball with two outs in the bottom of the ninth.

“Sometimes I give up a home run ball, too,” Rogoff smiled. With his 50 years in the business, I doubt that happens very often.

And never in the back seat of a Lincoln.

Start your Sunday with a laugh. Read the Sunday Funnies, fresh humor from The Out Of My Mind Blog. Subscribe now and you'll never miss a post.

Barry Rogoff began cutting diamonds in 1966, serving an apprenticeship at the world renowned diamond cutting works of Gustave Katz in Johannesburg, South Africa. In 1976, he moved to New York where I worked for Baumgold Brothers, Inc., for four years, a period he refers to as his second apprenticeship because of all the new tools and techniques I learned. Rogoff moved to Los Angeles in 1980, and met Yakov Kleyman. Four years later, the two established Barry Rogoff Diamond Cutters. In addition to diamond cutting, Rogoff has worked with GIA on a number of projects, including contributing to course materials for diamond cutting and serving on the Educational Advisory Committee. He’s hosted student field trips to his factory and made presentations to gemologist clubs on diamond processing.

Mind Doodle…

Twinkling in the sky, a mere 50 light years away, is a diamond star of 10 billion trillion trillion carats. If we could bring it down to Earth it would seriously outclass the largest diamond found on Earth, the 546-carat Golden Jubilee. On the other hand, you’d need a jeweler’s loupe roughly the size of the sun to grade the star diamond. Plus, a very large workbench on which to cut it.

The addendum was a clever way to get out greedy Congress to release more funding to NASA.

Hi Jeff…

Well, you caught me. Though I’m not sure how NASA will get that stone into the back seat of a Lincoln.