When I was a kid, the animated wind-up toy Mr. Machine was the answer to all my problems.

A mysteriously overturned ashtray? Blame it on Mr. Machine. A tomato juice spill on the carpet? Mr. Machine. Mysterious bruises on the arms of younger siblings?

You know who (or what).

It’s taken five decades, but Mr. Machine has finally been replaced by its digital equivalent.

The algorithm.

As for an algorithm’s content, you’d best prepare yourself for a Soylent Green moment.

Algorithms are appealing when it comes to shifting blame, partly because they are underwritten by the infallibility of mathematics and partly because they are rarely sent to the naughty corner when they screw up.

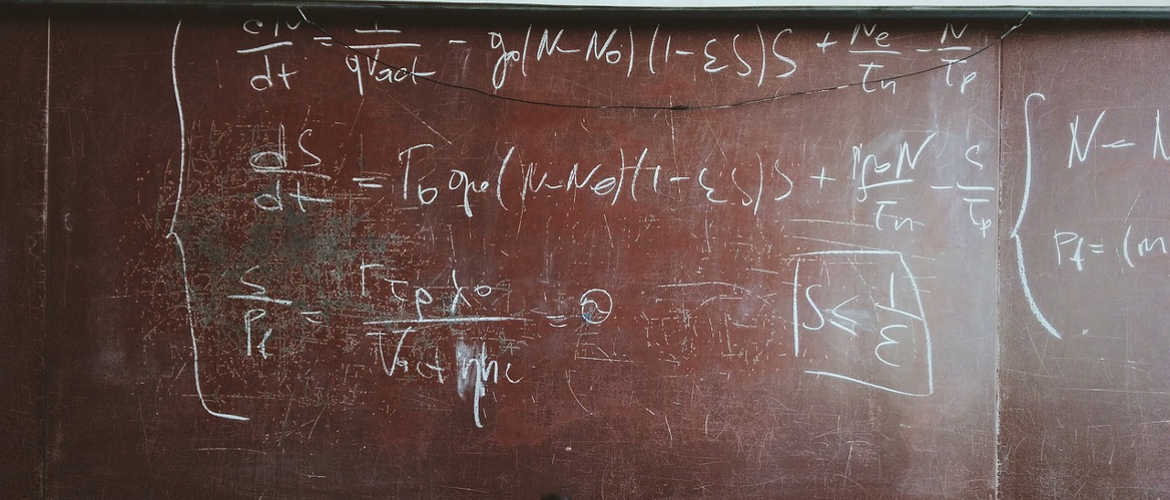

According to John MacCormick, author of Nine Algorithms That Changed the Future, “An algorithm is a precise recipe that specifies the exact sequence of steps required to solve a problem.”

A recipe. Like the one grandma used for her apple pie. Doesn’t that sound warm and friendly?

But there’s a difference.

These recipes are used by computers to manage everything from what news we read to whether radar blips are incoming North Korean missiles. Your grandma’s recipe might not make a tasty apple pie, but it’s not likely to start a nuclear war.

Which makes it somewhat important that we know what’s in these algorithms we depend on.

Before I can answer that question you need to understand why algorithms are a bit more complicated than recipes.

The word in MacCormick’s definition that sets algorithms apart is “precise.” Since computers don’t handle ambiguity well, all the steps in an algorithm must be exact. None of this “pinch of cinnamon” or “bake for 30 to 45 minutes” business. If an algorithm says “add 3” that means add exactly 3, not “a pinch of 3.”

Also, lacking a strong union, computers will work on a problem forever. To prevent such abuse, an algorithm must always come to an end.

Finally, an algorithm must provide an answer. Follow the recipe for apple pie and you’ll wind up with an apple pie, not an empty pie tin.

As for an algorithm’s content, you’d best prepare yourself for a Soylent Green moment.

Algorithms are people.

As Mark Hansen, statistician and director of the Brown Institute at Columbia University, put it in the Columbia Journalism Review, algorithms are “…the products of human imagination…They embed a series of assumptions about how the world works and how the world should work.”

But because algorithms carry the weight of mathematics (algorithm is a distortion of the name of Persian mathematician Mohammed ibn-Musa al-Khwarizmi), the word effectively cloaks the human fingerprints it contains.

If some fake news makes it to the top of Facebook’s newsfeed, it’s not the fault of some human decision maker, it’s the fault of a digital Mr. Machine.

Don’t laugh at the analogy.

Although algorithms are mathematical abstractions they’ve recently been the recipients of Mr. Machine’s most intriguing quality.

People credit algorithms with the ability to take actions.

“They drive cars. They manufacture goods. They decide whether a client is creditworthy. They buy and sell stocks, thus shaping all-powerful financial markets,” wrote Massimo Mazzotti in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

It’s a misunderstanding of mathematics and the misappropriation of language, and if it feels comfortable to you, the next time your partner cooks dinner downplay his or her role and praise the wonderful job performed by the recipe.

But, let’s go a step further. The technology of machine learning uses one set of algorithms to create new ones.

These new algorithms learn to win at poker. They also learn to discriminate between the radar echoes of a Boeing 777 and an incoming North Korean missile. But are they making decisions or reflecting the thinking patterns—and biases—of humans who have learned not to draw to an inside straight or that 777s can’t be missiles because they’re not long and straight?

Either way, there’s human DNA mixed into the digital evolutionary process from which these algorithms are born. But culpability, if any exists, is blamed on the math, not the people.

It’s like blaming the apple pie recipe if grandma said to use salt instead of sugar.

If you were allergic to certain foods, you’d ask what was in that apple pie before helping yourself to a slice. But few people ask what’s in the recipes that are increasingly responsible for their health, financial well-being, and safety.

We may never know exactly what’s in all these algorithms—the companies that use them treat them as trade secrets—but we can remind ourselves to question the human assumptions behind them as well as the answers they come up with.

Otherwise, we’re living our lives based on some pie-in-the-sky results.

Start your Sunday with a laugh. Read the Sunday Funnies, fresh humor from The Out Of My Mind Blog. Subscribe now and you'll never miss a post.

Mind Doodle…

Here’s a simple example of an algorithm that will open any combination lock ever made: try all combinations. Don’t laugh. It meets all the criteria. It’s precise, it always ends, and it always comes up with the combination. Not all algorithms are as practical as Mr. Machine.

Jay – when worked in instructional design at one of the biggest banks in the world, we developed loan officer training with the understanding that no matter what the algorithms said, the loan officer could overrule them with something called personal evaluation (gut instinct). Maybe the loan officers were just afraid that loan processing algorithms would just put them all out of business some day. In any event that was a long time ago. But I can’t help but wonder if that human element has been taken out of the loan processing equation completely these days. Algorithms vs intuition.

Hi Nick…

I’d answer yes to your question. In the early days, maybe a computer program would evaluate four or five factors before making a recommendation. That’s within the range of human calculation (or gut instinct). Now, there might be 30 factors, with complex interrelationships. There’s little chance of a human processing all of that.

What alarms me, though, is that other humans side with the computer, somehow believing that all that number crunching guaranttes the “right” answer.

— jay